Topic of the month September 2013: Discovering Sustainable Tourism

Discovering Sustainable Tourism

The tourism industry is flourishing worldwide, supported by falling travelling costs and increasing disposable incomes of many people. There are almost endless options to go on trips to explore other countries and cultures. Given the sensitivity of tourist destinations – especially in underdeveloped regions and natural environments – sustainable tourism is very important.

This issue of the Inrate Sustainability Matters points out the leverages that exist for stakeholders in the tourism industry, to foster long-term positive effects on the economy, local society and the environment. Furthermore, Inrate displays the sustainability performance of different stakeholders of the tourism industry. Which are the most sustainable options for tourists to choose from? Our two German travelling protagonists, Goethe in the 18th century and the fictitious Hermann in 2013, give it a try – and, as you will find out very soon, they are very differently successful with it.

In 1786, the German "Sturm und Drang" author Johann Wolfgang von Goethe experienced a personal crisis. He wanted to escape from his boring life and unsatisfactory relationship. So one night he broke up to an unknown destination without saying goodbye. After having passed Verona, Vicenza and Venice, Goethe finally reached the Italian capital of Rome in November.

Even today many of Goethe's countrymen feel a strong desire to travel. With per capita spending of 1023 US-dollars per year on holidays, Germany ranks second behind Australia, far ahead of many EU members. Also Hermann, who in 2013 is reading a book about the German wanderlust, becomes unstoppable, and via the Internet he books a last minute flight to the Maldives.

The tourism industry is rather stable – but is it also sustainable?

Not only thanks to German travelers has the tourism industry showed a growing trend. With increasing incomes, tourist expenditures increase even at faster rate than income. In contrast to many primary products, whose share in world consumption might decrease (UN 2013). The tourism sector has also shown to be less volatile than commodity revenue (Maloney and Montes Rojas, 2001), although hit by a series of incidents such as international terrorism, political instability, SARS and natural disasters. Tourism also brings much-needed foreign exchange, which allows developing countries to finance the import of capital goods and raw materials required for the economic development and diversification of their economies. Furthermore, tourism is a more diverse industry than many others, and as such has the potential to create income throughout a complex supply chain of goods and services (UN 2007).

Given these characteristics (see also Facts & Figures on next page) it is only natural that international tourism is one of the key industries selected by developing countries to drive economic growth. Hardly surprising also, considering the sector's potential to harness natural, cultural, and historical assets. Furthermore, the core of tourism is human capital – which is widely available in developing countries (CGGC 2011).

The growing importance of tourism activity in developing countries, however, faces the sensitivity of these economies. There is always the risk that negative effects of tourism overhaul the positive ones in the long run. On islands such as Tahiti or in the Caribbean, increased tourist flows create shortages with negative effects on the local population, for example increases in food prices, lodging problems or problems with water supply. Moreover, the local population does not always benefit from tourism revenues, because often a large share of the price that tourists pay for their holidays goes to multinational companies that own the airlines and run the hotels (UN 2007).

Sources: Inrate 2013. Data from World Travel & Tourism Council 2013 / World tourism organization (UNWTO) 2013 / UN 2013

Given this huge global relevance of the tourist sector, the sustainability performance of tourism is especially important. But what, actually, is sustainable tourism? The World Tourism Organization (WTO-OMT) defines it as follows:

"Sustainable tourism development meets the needs of present tourists and host regions while protecting and enhancing opportunities for the future. It is envisaged as leading to management of all resources in such a way that economic, social and aesthetic needs can be fulfilled while maintaining cultural integrity, essential ecological processes, biological diversity and life support systems."

In other words, sustainable tourism can produce the same profits as conventional tourism, with the difference that more of these profits stay with the local community. Besides, it helps to protect a region's natural resources and culture. As a result, sustainable tourism brings along benefits or opportunities for the future in a long-term perspective. Sustainable tourism deliberately seeks to minimize the negative impacts of tourism, while contributing to conservation and the well-being of the community, both economically and socially (UN 2013).

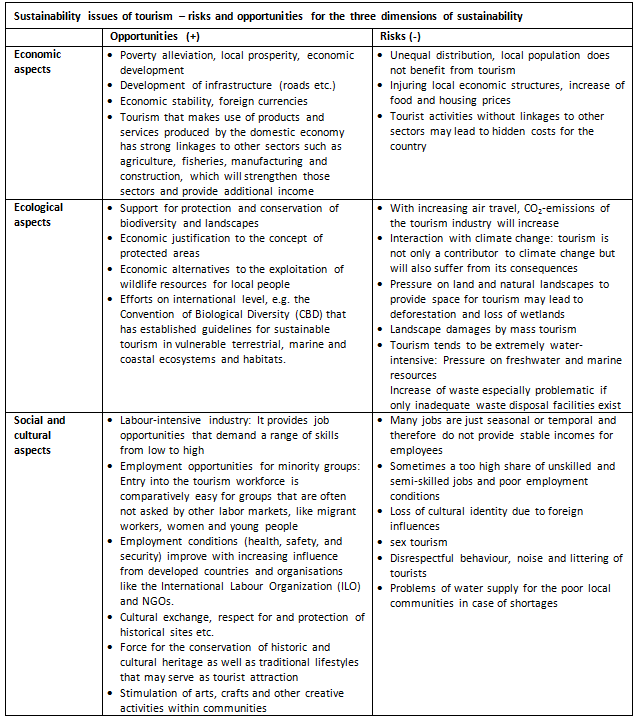

The following table lists the opportunities that may arise from tourism, but also the risks posed by non-sustainable tourism to local economies, societies and the environment.

Sources: Inrate 20013, based on UN 2013, UN 2009, UN 2007, UNEP 2005

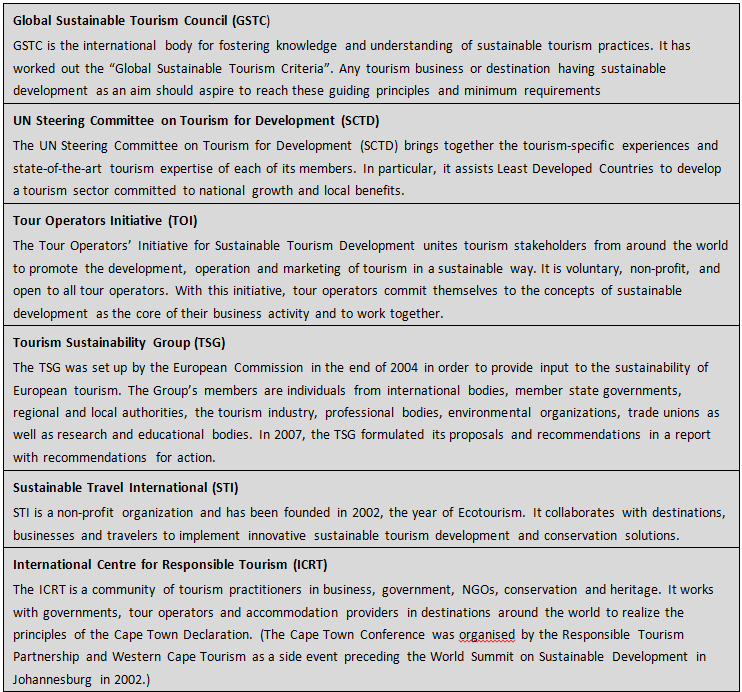

In the tourism sector itself, awareness about sustainability issues has developed significantly over the past 30 years. Different organizations have the objective to engage in an efficient manner towards a new decade of international support for sustainable tourism development. Their roles can range from spearheading sustainable tourism practices, to simply doing research in order to foster knowledge and understanding of sustainable tourism practices. Organizations, initiatives or roundtables that are currently active at an international level to foster sustainable tourism are listed in the grey box.

At their departure, both travelers – Goethe in 1786 and Hermann in 2013 – had no idea of what sustainable tourism means. Yet Goethe, who travelled mostly by stagecoach or on foot, behaved in principle sustainably, his trip was not polluting. Since he also tried to travel incognito, he was practically forced to adapt to local customs and traditions, and to respect them.

Hermann, however, would have arranged his trip a bit more sustainably, if only he had informed himself in advance about the multiple benefits of sustainable tourism. Arrived at a luxury hotel, he is annoyed that only Europeans are in sight and he got to eat pork knuckles. He would actually rather like to meet local people and support them. But what could he have done differently?

Along the value chain of tourism, sustainable options are available

According to recent studies, tourism can be made sustainable if it is deliberately planned from the beginning to benefit local residents, respect local culture, conserve natural resources, and educate both tourists and local residents (UN 2013). But where are the people responsible for that planning that should be done deliberately? And who is aware of what's best for local conditions?

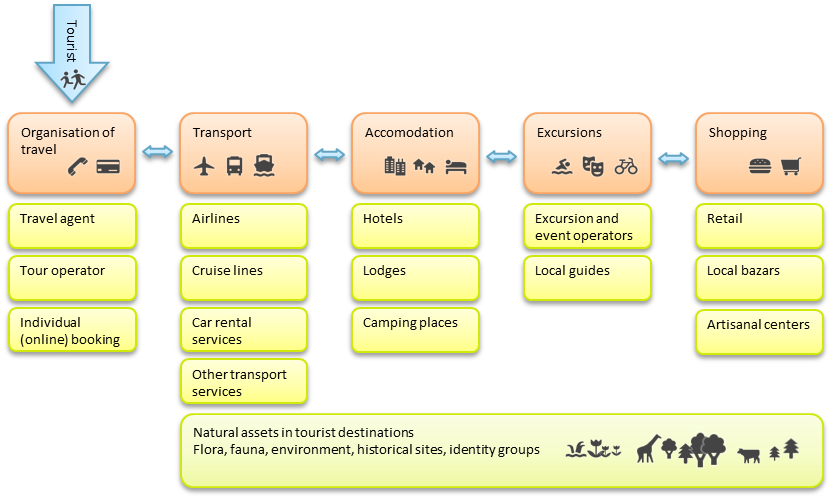

Unlike most other sectors, the consumer of tourism – the tourist – travels to the producer and the product. Therefore, on the demand side, the tourist himself can choose how his trip has to be configured, i.e. where to go, which means of transport to use, what kind of accommodation and which excursions he wants and so on. Opportunities to choose emerge basically from every step of the value chain of tourism (see grey box). The tourist is therefore directly able to pick the most sustainable options.

On the other hand, there are options of sustainable tourism products and services on the supply side. Responsible actors along the value chain of tourism, such as travel agents, transportation providers, hotels and resorts offer such products and services.

A major difficulty for sustainable tourism is the fact that there is often limited knowledge about which tourism product and services are the most sustainable ones. So even if a tourist tries to be as good informed as possible, it is difficult for him to choose the most sustainable option, because the preconditions of different tourism regions strongly vary. On the other hand, also suppliers of tourism products and services face the difficulty of insufficient information and knowledge about sustainability.

The global value chain of tourism

International and domestic tourists are the trigger or "input" for the global tourism value chain. Other than in production-based value chains, distribution is the first segment. Travel agents and tour operators, who offer travel arrangements, are the main distribution intermediaries. Tourists can also bypass intermediaries and book their trip components directly, e.g. by use of online booking systems, which became increasingly common in recent years. Depending on their preferences, tourists choose an appropriate mean of transport and accommodation, options range from the low-budget to the luxury version.

Once arrived at destination, tourists engage in a number of excursions like snorkeling, sailing, or surfing for beach tourists, which are the local activities representative of the tourism product and the natural assets of the destination. Excursions are provided by excursion operators and local guides. Furthermore, most tourists are engaged in shopping at destination or during transit, e.g. during visits of local bazaars or artisanal centers.

Figure 1: The global value chain of tourism. Some businesses supporting tourism such as food service, financial services, and computer reservation systems, are not visually represented. Source: Inrate (2013).

Air transportation is the fastest-growing source of greenhouse gases – but not the worst one

Choosing the means of transport is one of the first parts, whenever a holiday is planned. As an integral part of the tourism industry, the dynamics of the transportation sector is simultaneously a major cause and a very important effect of the growth in tourism: Tourism has expanded due to the improvement of transportation, as tourism cannot thrive without travel.

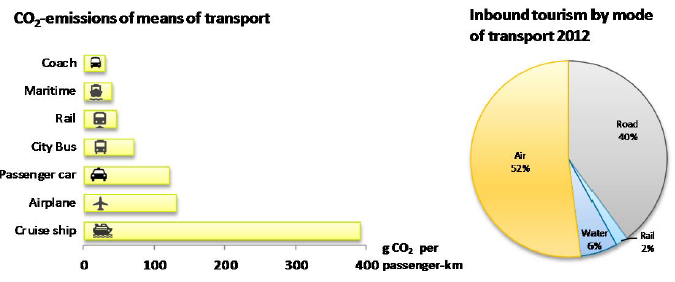

Recent statistics recognize tourism as contributing 5% to total global CO2-emissions (UNWTO/UNEP/WMO 2008), and 90% of these total greenhouse gas emissions are related to transportation (Howitt et. al 2009). Regarding the fact that tourism accounts for 9% of global GDP (WTTC 2013), the CO2-intensity of the tourism industry (i.e. CO2-emissions per turnover) seems to be rather low at first sight. However, when taking into account the strong dynamics and rapid growth of the tourism sector, especially the projections of around 5% annual growth in air travel (Boeing 2005), the worldwide tourism industry bares the risk to become much more CO2-intensive in future.

Air transportation is at the time the fastest-growing source of greenhouse gases. Especially low fares for flights have led to an increased number of people choosing the airplane, allowing them to travel far more cheaply over long distances than by rail or road. Growth rates of international air traffic are pegged with growth rates of international tourism (Rodrigue 2013). From an environmental perspective, this trend is rather regressive, because aviation is well-known as being carbon-intensive. But even if you choose to fly, there are ways to reduce your impact by choosing an airline that implements fuel efficiency measures and other initiatives to reduce its impacts. There are many ways CO2-emissions of flights can be reduced, e.g. by avoiding routes with stopovers (because during take-off and landing the highest emissions occur), by choosing efficient planes and maximum seating in combination with high load factors etc. (atmosfair Airline Index 2012).

Another option is to offset the CO2-emissions of the flights by buying CO2-certificates of carbon offset projects. Such projects are rather controversial – opinions of experts about their effect range from "cleanse of sin" to "effective, and economically the best solution". Therefore, carbon offsetting can only be considered to be the second-best solution to the option not to fly at all. Still, the support of carbon offset projects can at least contribute to sustainable development in the project regions, which are often developing countries.

On a beautiful day at the beach, still frustrated with his wrong decision, Hermann surfed with his tablet on the internet. So he came across a YouTube video about the high CO2- emissions of aircrafts. Even more frustrated that not even for travelling he had chosen the best - that is the most sustainable - option, he decided not to take his flight back home. Instead, he extended his vacation and booked a travel by cruise ship back to Germany.

But how does it actually look, if one decides to take a long-term journey on a cruise ship? According to the study from Howitt et al., cruise ships exhibit an emission factor of 390g CO2 per passenger km. This is approximately three to four times more than emissions factors of aircrafts. The huge carbon intensity of cruises is a not well-known fact: The misconception of the carbon impact of cruise vessel may arise due to the shipping of international cargo, which is by far less carbon-intensive than air freight (Howitt et al. 2010). But compared to freight and passenger transportation by airplanes, cruise ships are not very densely packed. The space needed per passenger is huge and very often the cruise trips are not fully booked. In addition, cruise ships entail additional greenhouse gas emissions from included services such as accommodation and leisure activities. For example, the energy use of the "hotel function"[1] in a cruise ship is about five times higher than the average energy use for the most luxurious of onshore hotels per visitor night, which would include many of the same amenities as a large cruise vessel, such as swimming pools, casinos, gyms and restaurants (UNWTO/UNEP/WMO 2008, Howitt et al. 2010).

Nevertheless, cruise shipping has become a significant tourist industry. Big cruisers are like floating resorts where guests can enjoy luxury and entertainment while moving towards their destinations. For that reason tourists spend most of their money on the cruise ship itself (gift shops, entertainment, casinos, bars, etc.) or on island facilities owned by cruise shipping companies. Thus, the potential positive impacts of cruising on the local economy are mitigated as the strategy of cruising companies is to retain as much income as possible with them (Rodrigue 2013). The development of the cruise shipping industry may therefore lead to a disadvantage for some traditional tourism regions, as tourists spend most of their money on the ship.

Source: Inrate (2013), based on data from European Environment Agency / UNWTO 2013: UNWTO Tourism Highlights, 2013 Edition.

[1] Approximately two-thirds of the energy use and emissions produced by a cruise line comes from the transportation task of the cruise vessel and the remaining one-third comes from the auxiliary vessel, which provides power for the electrical demand onboard, the "hotel function" and leisure activities (Howitt et al. 2010).

Hotels are very large consumers of resources

The hospitality industry spends 3.7 billion USD a year on energy and a typical hotel uses 826 litres of water per day per occupied room. For that reason, whether staying for a weekend or longer, it is very important that the accommodation takes efforts for reducing its environmental impacts and strives for environmentally conscious businesses whenever possible.

Especially when travelling in developing countries, it is important that the hotel, lodge or other accommodation has a positive impact on the local supply chain and local people. Money generated by tourist hotels does not always benefit the local community, as some of it leaks out to huge international companies that do not integrate local communities into their business. Sustainable businesses on the contrary hire employees from neighboring towns, pay them fair wages, and offer them additional training to develop the needed skills.

But how can tourists know what accommodation is sustainable? Many hotels have demonstrated their commitment to sustainability by participating in a sustainable tourism certification or verification program. Certification is a mechanism for ensuring that the accommodation meets certain standards (RESET 2013). This means that they have been audited by an independent, third-party program and have met a set of environmental, social, and economic criteria (SustainableTrip 2013). Even without providing such certifications, accommodation providers can take action to prevent unnecessary energy and water consumption in hotel rooms, e.g. by providing automatically regulated air conditioning, and limited water availability in case of scarcity. However, if there is not much information available on those issues, the best choice a tourist can pick are often locally-owned hostels and lodges.

Two years after his disappearance, Goethe returned to Germany. He told of the troubles of his journey, but also about the fascinating beauty of the country and the culture that needs to be protected. Hermann, however, back home after a full month of holidays, notes with horror that he has actually experienced nothing unusual in the two weeks on the cruise ship – except maybe the incredibly beautiful sunsets over the sea. Therefore he rather tells his friends about his latest interests for sustainability. Based on studies of the rating agency Inrate, he recently found out that sustainability criteria can be considered not only in tourism but virtually in every economic sector – and that different companies apply them quite differently...

Inrate shows: companies in the tourism industry foster sustainability

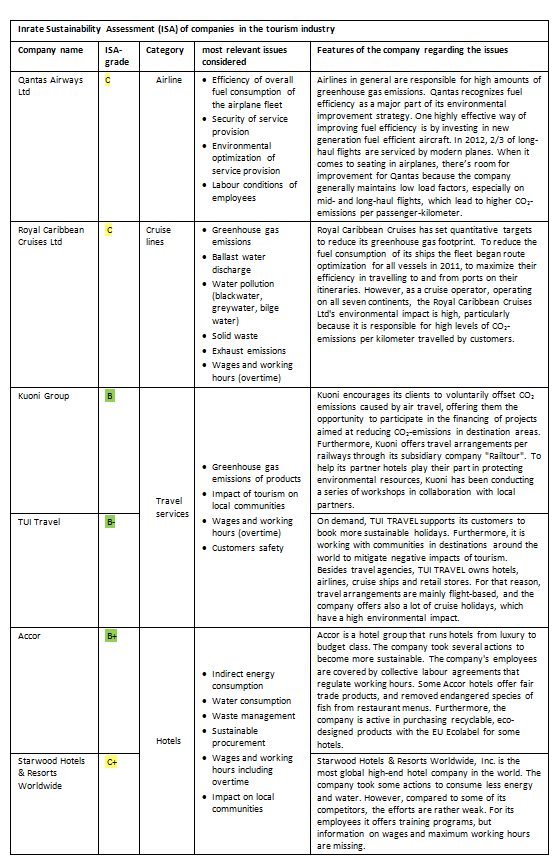

Inrate has developed a method, the Inrate Sustainability Assessment (ISA), which measures the environmental and social impacts a company has through its products and practices, as well as the company's willingness and ability to effectively address the related sustainability issues it faces.

First of all, the ISA analyzes the environmental and social impacts of the products and services provided by the company, taking into account every step on the value chain from manufacturing to disposal.

For each activity of the company, most relevant sustainability issues are defined. For companies that are active in the tourism industry, relevant sustainability issues are for example overall fuel consumption of the airplane fleet operated (efficiency), working hours and overtime of employees, impact of tourist operations on local communities, as well as customers' safety. In a next step, Inrate analyses the measures a company has taken to mitigate the impacts of its activities. The measures can be categorized in policies, commitments, targets, initiatives, and improvement programs.

Apart from the specific sustainability issues, generally important criteria to foster a sustainable development are considered during the ISA-process as well, for example the company's environmental and social management, including energy consumption and water and waste management, as well as labor conditions and health and safety management of employees. In this respect, controversial and unethical business practices are considered as well.

Information used in the rating process stem from the companies' own reporting as well as from external sources, and are carefully analyzed and assessed according to the ISA methodology.

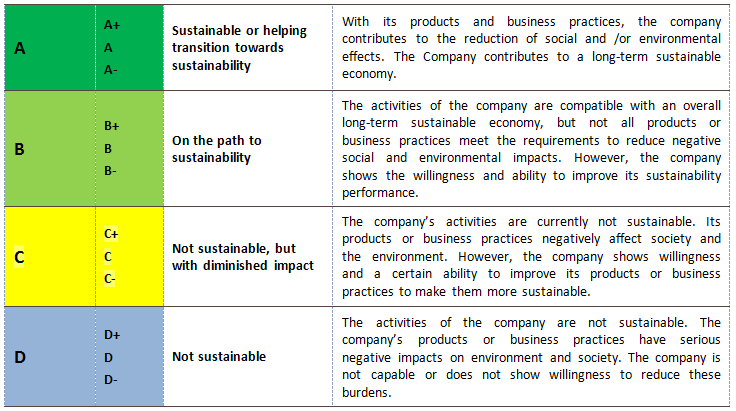

The result of the ISA is an absolute grade of the sustainability performance of the company on a scale from A+ to D-:

Amongst the series of players in the tourism industry which are assessed by Inrate's sustainability assessment (ISA) you will find Qantas Airways, Royal Caribbean Cruises Ltd., Kuoni Group, TUI Travel, Accor and Starwood Hotels & Resorts Worldwide. They are listed in the table below with final grades given by Inrate. You also find the issues considered and a short description of the companies' most important characteristics from a sustainability perspective.

References:

- atmosfair 2012: atmosfair Airline Index 2012. Berlin.

- Boeing 2005: Current Market Outlook 2005. Seattle

- CGGC 2011: Duke, Center on Globalization, Governance & Competitiveness: The Tourism Global Value Chain. Economic Upgrading And Workforce Development. Michelle Christian Karina Fernandez-Stark, Ghada Ahmed, Gary Gereffi, November 2011.

- European Environment Agency (EEA) 2013

- Global Sustainable Tourism Council (GSTC) 2013

- Howitt O., Revol V., Smith I., Rodger C. 2009: Carbon emissions from international cruise ship passengers' travel to and from New Zealand. Departement of Physics, University of Otago, Dunedin.

- ILO 2010: "Developments and challenges in the hospitality and tourism sector". Paper presented at theGlobal Dialogue Forum for the Hotels, Catering, Tourism Sector

- International Centre for Sustainable Tourism (ICST) 2013

- RESET (2013)

- Rodrigue J., (2013): The Geography of Transport Systems. New York.

- Sustainable Travel International (STI) 2013

- SustainableTrip (2013)

- Tourism Sustainability Group (TSG) 2013

- Tour Operators Initiative (TOI) 2013

- UN 2007: Is the concept of sustainable tourism sustainable? Developing the sustainable tourism Benchmarking Tool. Lucian Cernat and Julien Gourdon, United Nations, New York and Geneva, 2007. UN-Publications ISSN 1816 – 2878.

- UN 2013: Sustainable tourism: Contribution to economic growth and sustainable development. Issues note prepared by the UNCTAD secretariat. Trade and Development Commission Expert Meeting on Tourism's Contribution to Sustainable Development Geneva, 14–15 March 2013.

- UNEP 2009: Sustainable Coastal Tourism. An integrated planning and management approach. Priority Actions Programme Regional Activity Centre (PAP/RAC).

- UNEP 2005: Making Tourism more sustainable

- UNEP Tourism Program website: United Nations Environmental Program Production & Consumption Branch.

- UNWTO 2013: UNWTO Tourism Highlights, 2013 Edition.

- UNWTO/UNEP 2012: Tourism in the Green Economy – Background Report. Madrid.

- UNWTO 2012: World Tourism Organization (UNWTO) (2012). UNWTO Tourism Highlights: 2012 Edition. UNWTO. Madrid.

- UNWTO 2011: Report of the World Tourism Organization to the United Nations Secretary-General in preparation for the High Level Meeting on the Mid-Term Comprehensive Global Review of the Programme of Action for the Least Developed Countries for the Decade 2001-2010

- UNWTO/UNEP/WMO (2008): Climate Change and Tourism: Responding to global challenges. Madrid.

- European Environment Agency: The main transport modes used

- World Travel & Tourism Council 2013: The Authority on World Travel & Tourism. Economic Impact of Travel & Tourism 2013 Annual Update: Summary.

- WTTC 2013

| Authors: Judith Reutimann & Gina Spescha, Senior Analysts, Inrate Lt. |

Inrate Ltd is a leading independent sustainability rating agency active in Europe. It is based in Switzerland and has more than 20 years of experience in linking its know-how on sustainability with the financial markets. Inrate provides tailor-made solutions for investors who wish to consider ESG issues in their investments – either on the grounds of socially responsible investment or with the aim of minimizing extra-financial risks in traditional investment. More information: www.inrate.com.

-----------------------

Notice and Disclaimer:

The assessments and data reported above are offered by Inrate for informational purpose or for being used by financial professionals. They are in no way recommendations to invest or disinvest in any financial product. They must not be understood as a financial forecast of financial performance of underlying securities. © All rights are reserved. The entire paper and its parts are protected by copyright. Utilizations other than those legally permitted need prior written permissions from the authors.

More information