Topic of the month October 2013: Natural resources tug-o-war

Natural resource tug-o-war: The South African mining industry, water scarcity, and biodiversity

On October 1-2, the sustainable investment community converged on Cape Town, South Africa for the PRI in Person conference to discuss the environmental, social and governance issues affecting the country. From the perspective of MSCI ESG Research, one of the most significant issues affecting South Africa’s growth will be socio-economic conflict resulting from water resource scarcity. In a country that is already experiencing a scarcity of potable water, population growth and climate change threaten to increase the risks of water shortages and community land conflict for companies and society.

The engine that drives South Africa’s economy is fuelled by natural resources. Primary minerals account for almost 40% of South Africa’s total exports1, which has significant implications on the South African rand and current account balance. The mining industry gains even more importance during periods of high commodity prices, which also contributed to the 61% increase in the number of mines between 2005 and 20132. However, South Africa’s reliance on the mining industry comes with significant social and environmental risks. The labor strikes that rocked South Africa’s mining sector in August 2012 made this even more apparent, as global platinum prices experienced a short-term price shock and investor faith in the country’s security deteriorated. With careful management, South Africa can repair its industrial relations and re-ignite the economy, but the hard barrier to growth, which is largely irreversible, is resource scarcity.

South Africa’s natural resource-dependent economy is complicated by the fact that exploitable resources overlap with stressed water sources and biologically rich lands. This inconvenient resource allocation increases the likelihood of unmet demand and conflict:

- Approximately one-third of South Africa’s territory receives adequate rainfall for agriculture, but only a third of that land is fertile.3

- The Limpopo province has the second-highest percentage of agricultural households in South Africa (33% of total households), and also contains the world’s largest platinum reserve.4

- The Karoo Basin, which spans much of central and southeastern South Africa, sits on top of one of the world’s largest shale gas reserves, but is faced with year-round water scarcity – posing a clear challenge to the water-intensive extraction process.

Mining companies, society, and water risks

South Africa is highly dependent on irrigated crops, which is primarily due to the lack of rainfall and depletion of key ground water resources in South Africa’s primary agricultural and ranching hub, the Limpopo region. Here, farmers are faced with severe scarcity from July through November, as the water demand from irrigation comes dangerously close to the supply limitation. Additionally, the highly erratic, short rainy season poses a challenge for subsistence farmers that do not have the means to invest in irrigation equipment. Overall, irrigation accounts for over 60% of South Africa’s total water withdrawals5, according to the last Water Accounts survey – a fact that is largely attributed to the inconvenient distribution of fertile land and rainfall.

While the agricultural sector faces a resource allocation problem with rainfall and fertile land occurring in different regions, it is the intra-sector conflict with mining that could have a longer lasting impact on South Africa’s resources and economy.

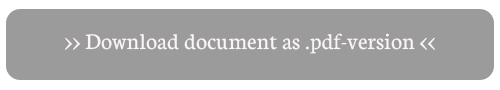

Figur 1: Mines and Land Use in South Africa’s Limpopo Basin

Source: MSCI ESG Research, GLOBCOVER by ESA/UNEP/FAO/JRC/IGBP/GOFC-GOLD; SNL Metal Economics Group; Hoekstra, A.Y. and Mekonnen, M.M (2011) Global water scarcity: monthly blue water footprint compared to blue water availability for the world’s major river basin, Value of Water Research Report Series No. 53, UNESCO-IHE, Delft, the Netherlands.

The most pressing issue facing South Africa’s extractives industry is the overlap between the country’s precious metals deposits and fertile agricultural land. Approximately 43% of all assets of precious metals companies in the MSCI All Country World Index (MSCI ACWI) are located in South Africa.6 Of South Africa’s primary minerals, platinum group metals (PGMs) are the most concentrated in the Limpopo basin and have the highest proximity to key crops and grazing land, which puts even greater pressure on South Africa’s most stressed, and economically-important groundwater source (Fig. 1). While platinum mining companies are no stranger to conflict, increased demands on a stressed water resource has the potential to cause production disruptions due to water shortages, land disputes with local communities, and groundwater contamination that can linger for decades, long after mines are closed.

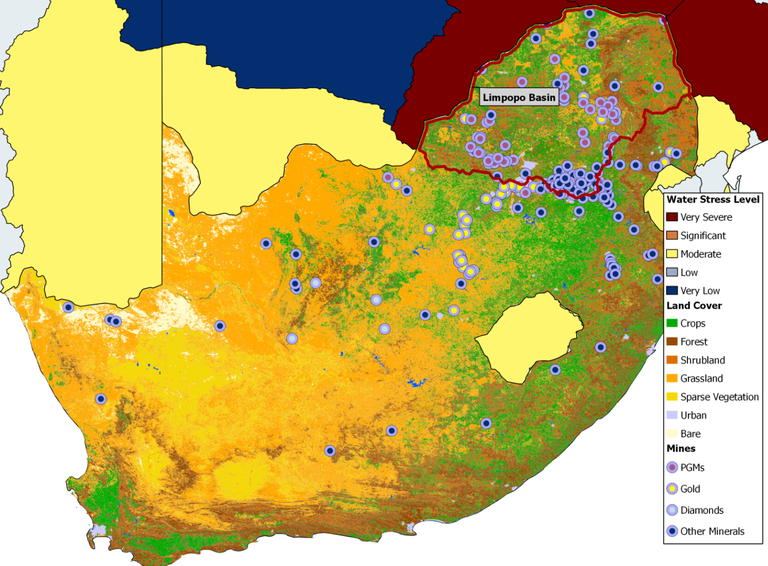

Figure 2: Percentage of Companies in the Precious Mining Industry That Have Committed to Water Reduction Targets, by MSCI Index Constituents

Source: MSCI ESG Research

Generally, South African companies have exhibited a high degree of awareness and action on water issues, as demonstrated by the fact that over half of the precious metals and gold companies in the MSCI South Africa Investable Market Index (MSCI ZA IMI) commit to quantifiable water reduction targets, far above the 8% average for MSCI World companies (Fig. 2). Although extractive companies in South Africa have had stronger water management strategies than global peers, we still have concerns that large mining operations are at risk of suffering operational disruptions due to community conflict over shared water resources.

Mining growth threatens ecological integrity

According to the Convention on Biological Diversity, South Africa is the third-most biologically diverse country in the world after Brazil and Indonesia. Together, these three countries represent two-thirds of all biodiversity globally.7

The main risks associated with resource exploitation in biologically-rich regions are a loss of or difficulty in obtaining regulatory permits, compensation demands, reputational damage, litigation, community opposition, and loss of social license to operate. In addition, as natural resources and populations of threatened species decline due to poor management and over consumption by growing populations and industry alike, the costs to protect biodiversity or compensate for destruction will increasingly burden companies. Biodiversity loss due to cultivation, mining and urban expansion is projected to result in the loss of all natural habitat outside protected areas in Gauteng, North West and KwaZulu-Natal by 2050.8

In South Africa, the perceived and real systemic risks have created widespread public opposition to unconventional extraction practices especially when entering new ground, such as the case with hydraulic fracturing in the water scarce Karoo Basin.9

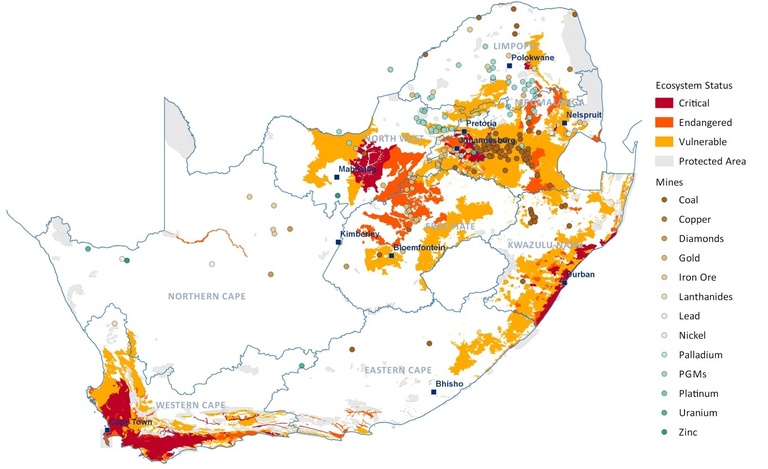

Figure 3: Mining and Ecosystem Status

Source: MSCI ESG Research, South African National Biodiversity Institute

MSCI ESG Research analysis shows that the industries contributing most to biodiversity loss and land use change in South Africa include the integrated oil and gas, coal and consumable fuels, steel, paper products, and mining industries. Of the industries at risk, metals and mining companies are the most exposed. Figure 3 shows the mining constituents listed on the MSCI South Africa IMI and their location across the northeastern part of South Africa relative to the ecological status and protected areas. Many fall within or near endangered and critical ecosystems and with the number of mines having nearly doubled between 2004 and 2011, the risks associated with biodiversity and intensified mining operations and expansion will likely increase in the South African context.

Resource scarcity favors efficiency

The combination of population growth (1.2% CAGR between 2008 and 2012)10 and South Africa’s reliance on natural resources could increase the demands on water and biological resources beyond their sustainable limits, likely resulting in regulatory restrictions to alleviate the societal costs of resource extraction. For the inefficient resource user, this represents a significant business risk, but for the companies that have fundamentally integrated resource efficiency into their operations, it represents an opportunity to establish a new economic stasis with society.

References:

- 1 Chamber of Mines of South Africa. Facts & Figures 2012. 2012

- 2 Paul Vecchiatto, “Shabangu defends government’s track record with mining industry,”BDlive. February 5 2013 (Accessed September 24 2013).

- 3 WWF. Agriculture: Facts & Trends South Africa. 2012

- 4 Statistics South Africa. Census 2011 Agricultural Households. Report No. 03-11-01. 2011

- 5 Statistics South Africa. Updated Water Accounts for South Africa: 2000. Discussion document – D0405 December 2006

- 6 MSCI ESG Research. Water Issue Report: Upstream and Downstream Impacts from a Well Running Dry. September 2013

- 7 Government Communication and Information System, Pocket Guide to South Africa, Environment, 2011/12

- 8 South African National Biodiversity Institute. Life: The State of South Africa’s Biodiversity 2012. South AfricanNational Biodiversity Institute, Pretoria. 2013

- 9 Paul Burkhardt, “Karoo is centre of energy dilemma,” BDlive. August 28 2013 (Accessed September 24 2013)

- 10 World Bank. 2013. World Development Indicators Online (Data retrieved September 24 2013)

| Authors: Cyrus Lotfipour & Daniel Rogatschnig Senior Analysts, MSCI ESG Research |

For further Information on MSCI ESG Research please visit www.msci.com/esg or contact ESG Client Service esgclientservice@msci.com.

Notice and Disclaimer: This document and all of the information contained in it, including without limitation all text, data, graphs, charts (collectively, the “Information”) is the property of MSCI Inc. or its subsidiaries (collectively, “MSCI”), or MSCI’s licensors, direct or indirect suppliers or any third party involved in making or compiling any Information (collectively, with MSCI, the “Information Providers”) and is provided for informational purposes only. The Information may not be reproduced or redisseminated in whole or in part without prior written permission from MSCI.

The Information may not be used to create derivative works or to verify or correct other data or information. For example (but without limitation), the Information may not be used to create indices, databases, risk models, analytics, software, or in connection with the issuing, offering, sponsoring, managing or marketing of any securities, portfolios, financial products or other investment vehicles utilizing or based on, linked to, tracking or otherwise derived from the Information or any other MSCI data, information, products or services.

The user of the Information assumes the entire risk of any use it may make or permit to be made of the Information. NONE OF THE INFORMATION PROVIDERS MAKES ANY EXPRESS OR IMPLIED WARRANTIES OR REPRESENTATIONS WITH RESPECT TO THE INFORMATION (OR THE RESULTS TO BE OBTAINED BY THE USE THEREOF), AND TO THE MAXIMUM EXTENT PERMITTED BY APPLICABLE LAW, EACH INFORMATION PROVIDER EXPRESSLY DISCLAIMS ALL IMPLIED WARRANTIES (INCLUDING, WITHOUT LIMITATION, ANY IMPLIED WARRANTIES OF ORIGINALITY, ACCURACY, TIMELINESS, NON-INFRINGEMENT, COMPLETENESS, MERCHANTABILITY AND FITNESS FOR A PARTICULAR PURPOSE) WITH RESPECT TO ANY OF THE INFORMATION. Without limiting any of the foregoing and to the maximum extent permitted by applicable law, in no event shall any Information Provider have any liability regarding any of the Information for any direct, indirect, special, punitive, consequential (including lost profits) or any other damages even if notified of the possibility of such damages. The foregoing shall not exclude or limit any liability that may not by applicable law be excluded or limited, including without (as applicable), any liability for death or personal injury to the extent that such injury results from the negligence or willful default of itself, its servants, agents or sub-contractors. Information containing any historical information, data or analysis should not be taken as an indication or guarantee of any future performance, analysis, forecast or prediction. Past performance does not guarantee future results. None of the Information constitutes an offer to sell (or a solicitation of an offer to buy), any security, financial product or other investment vehicle or any trading strategy.

You cannot invest in an index. MSCI does not issue, sponsor, endorse, market, offer, review or otherwise express any opinion regarding any investment or financial product that may be based on or linked to the performance of any MSCI index. MSCI’s indirect wholly-owned subsidiary Institutional Shareholder Services, Inc. (“ISS”) is a Registered Investment Adviser under the Investment Advisers Act of 1940. Except with respect to any applicable products or services from ISS (including applicable products or services from MSCI ESG Research, which are provided by ISS), neither MSCI nor any of its products or services recommends, endorses, approves or otherwise expresses any opinion regarding any issuer, securities, financial products or instruments or trading strategies and neither MSCI nor any of its products or services is intended to constitute investment advice or a recommendation to make (or refrain from making) any kind of investment decision and may not be relied on as such. The MSCI ESG Indices use ratings and other data, analysis and information from MSCI ESG Research. MSCI ESG Research is produced by ISS or its subsidiaries. Issuers mentioned or included in any MSCI ESG Research materials may be a client of MSCI, ISS, or another MSCI subsidiary, or the parent of, or affiliated with, a client of MSCI, ISS, or another MSCI subsidiary, including ISS Corporate Services, Inc., which provides tools and services to issuers. MSCI ESG Research materials, including materials utilized in any MSCI ESG Indices or other products, have not been submitted to, nor received approval from, the United States Securities and Exchange Commission or any other regulatory body.

Any use of or access to products, services or information of MSCI requires a license from MSCI. MSCI, Barra, RiskMetrics, IPD, ISS, FEA, InvestorForce, and other MSCI brands and product names are the trademarks, service marks, or registered trademarks of MSCI or its subsidiaries in the United States and other jurisdictions. The Global Industry Classification Standard (GICS) was developed by and is the exclusive property of MSCI and Standard & Poor’s. “Global Industry Classification Standard (GICS)” is a service mark of MSCI and Standard & Poor’s.